Access to Sleep Care: Part I

The American Alliance for Health Sleep (AAHS) recently published their executive summary on their recent Access to Care Survey, specifically related to sleep. Although the number of participants was relatively small for this type of questionnaire, there were still some interesting critiques to be made about their efforts. In addition, I will also comment on some ideas for future surveys that might reveal a deeper understanding regarding the problems with access to sleep care.

To start, the key conclusions of the AAHS Executive Summary involved those issues affecting an individual’s ability to access quality sleep, including:

- Cost of care and coverage by insurance companies

- Access to providers, both PCPs educated on sleep disorders as well as available sleep specialists

- Limitations of currently available treatments

- Access to accurate information online or from medical professionals

They provided a few central recommendations, including improving:

- Access to sleep services for those suffering with sleep disorders

- Awareness of general population that would benefit from increased education

- Additional education for providers and the public

- Availability of reliable and accurate information about sleep disorders online

- Research on sleep disorder treatment, insurance coverage and decreasing patient costs

As their conclusions and recommendations overlap, the discussion will naturally weave together the problems and the proposed solutions.

First and foremost they point out the issues related to cost and insurance coverage for sleep disorders treatment. However, in their solutions the only point made was the need for research on decreasing costs. Not having access to their full report, which is only available to AAHS members, I cannot be certain what else was mentioned on the topic of finances and insurance coverage.

Notwithstanding, as I have described in a prior post, the fastest way to lower costs in the sleep market would be to remove all insurance coverage for evaluation and treatment except for those who fall below some threshold that would merit safety net status. For the vast majority of individuals in the middle class or above, if no insurance coverage were provided for sleep medicine services, the costs would naturally drop into the basement in short order. Such a decrease should not be a surprise when you consider how much time in sleep medicine is spent on administrative actions and related paperwork. Moreover, think about the oddity in sleep medicine where a patient doesn’t simply receive a prescription and then heads to the pharmacy to pick it up. Instead, there are so many clinical and administrative steps that must be traversed.

What if there were no such thing as insurance coverage for sleep services? How would DMEs operate if they had fewer hassles to manage in dealing with insurance carriers, who currently grant permission for the device to be authorized to a particular patient, based on specific criteria? What if instead, the patient completes sleep testing, the doctor writes a prescription for PAP, and the patient contacts the DME company to move forward. And, when the patient is “shopping” at the DME, the individual can learn about prices as well as the unique capacities of the different types of PAP modes. Just like in any other shopping experience, the patient (now functioning like a consumer) gets what they pay for. For some, the perfect fit might be a standard CPAP with no bells and whistles. For others, a choice might be made for APAP or BPAP. Still others, familiar with our research, might want to pursue more advanced PAP devices such as ABPAP or ASV.

In going through this process, DMEs would compete with other DMEs for market share, and the prices of all PAP devices would decrease. Once you bring in competition, all sorts of other program innovations develop. For example, in the big picture encompassing all the oddities of trying to use PAP therapies, it should have been readily apparent years ago that an essential component to success would be a highly sophisticated device loaner operation.

With loaner devices, patients experience a great deal less pressure in learning how to use PAP as well as when they are trying to adapt to it. A loaner program means patients could pay a small out of pocket expense for both a used PAP machine and properly cleaned and pasteurized used masks and tubes. The patients would be set up with the devices the morning after their first diagnostic study in the case of the HST model of care, or after their first titration night in the sleep lab. In either setting, momentum is maximized, and the patient appreciates a straightforward, how-to type program. Compare the immediacy of just these features with what so many patients suffer through in the context of sleep medical centers and DMEs hassle back and forth, after which the DMEs and insurers hassle back and forth. All the while, an uncertain patient (sometimes 50% of OSA cohorts) loses whatever momentum had been originally gained at first exposure to a sleep therapy process.

Since I do not have access to the AAHS full survey, I do not know for certain whether or not they address the invaluable potential for out of pocket programs, driven by direct patient care. Far and away this step alone would lead to the cheapest possible prices for PAP modes and supplies, and it would also lead to marked reductions in the costs for clinical sleep medicine services. One of the best examples of the latter price reductions involves the use of sleep technologists to facilitate daytime clinic appointments.

Much of what goes on in any daytime clinic appointment regarding PAP therapy would be the hands-on work of fitting masks, solving mask leak and mouth breathing issues, educating patients on consistently and properly placing the mask and how to clean the equipment. The other major parameter would be the fine tuning of pressure settings, which nowadays can be interpreted and implemented through the downloading of detailed data reports directly from the PAP machine. With the data readily available, the two most important metrics to analyze are usually related to the persistence of leak or residual flow limitation events or both. A sleep tech under the supervision of a sleep specialist can easily solve 80% or more of these issues, draft a brief encounter note, after which the physician or other supervising provider can sign off and recommend further adjustments.

We along with many other sleep centers in the USA are already engaging sleep technologists in this manner, and the patients love the encounters, because sleep technologists possess so much more hand-on experience compared to sleep physicians. Yet, the pricing on these appointments is higher at this point due to the insurance-driven market, because all the administrative issues create more unnecessary labor. Moreover, several controversies still arise about how to bill for sleep tech appointments. Get insurance out of the equation, and then patients and sleep centers will work directly with each other to find the most competitive prices that still yield quality of care.

Another large area of concern involved the current and future education levels of both providers, including PCPs, as well as the public. AAHS expressed concerns about how well educated are our current PCPs on providing accurate information on assessment and treatment of sleep disorders and how smooth is the access to those providers that actually know enough about sleep disorders to steer patients into the right direction. From the opposite end, what is being done to educate patients and the public at large on the depth and breadth of health problems linked to undiagnosed and untreated sleep disorders, which supposedly would motivate them to seek treatment?

This area is of course huge, perhaps limitless, and again my comments are only based on the AAHS executive summary not their in-depth report. Of related interest, I recently conducted one of those “thought leader” interviews, during which a consulting firm pays me for an expert opinion on various topics regarding OSA. In this interview, a lot of the questions were directed at the basics of sleep medicine, that is, how does someone get referred to a sleep doctor, how does someone get diagnosed with sleep apnea, and what are the main treatment options. Interspersed with all these questions were corollary follow-ups all regarding education of doctors and patients. For example, how well is the public educated on the idea of a field of sleep medicine, or how might doctors convince patients of the importance of diagnosing and treating sleep problems, or finally, how aware are physicians of the various treatment options for OSA and why someone would select one option over another.

Repeatedly, I pointed out the education dilemma is driven by the overarching and constraining conventional wisdom that demonstrates an utter lack of respect for sleep in general and the field of sleep medicine in particular. This point cannot be driven home long enough, wide enough or deep enough; it is the fundamental issue here (i.e. absence of respect for sleep) that continues to expand, yet the field of sleep medicine has not expanded its capacity to keep up with the epidemic of sleep disorders in the population.

Two converging points of view serve as the drivers that create this dilemma. The first, from the professional perspective, is that doctors go to medical school and complete residency and all the while suffer severe sleep deprivation. Thus, from their living experiences of 4 to 12 years in duration, they are either indoctrinated into the belief that sleep is worthless or they already believed this notion before school, such that school merely confirmed their position. The second refers to a similar set of circumstances regarding people going about their everyday life, where routinely we see those clamoring for more sleep are labeled as lazy, slothful, or unproductive compared to those who have the capacity to get by on less sleep, either naturally due to genetic predispositions or artificially through regular use of stimulants, notably caffeinated beverages.

At the intersection of these professional and public viewpoints, you can turn left or right or go straight, but they only lead you to dead ends. Why? Because the degree of disrespect for sleep and thereby the disrespect for the field sleep medicine or what is often called the “Rodney Dangerfield of medical subspecialities” prevents both the public and the medical profession from embracing what arguably should be considered the next most important vital sign after breathing, pulse, blood pressure and temperature. Some have called pain the 5th vital sign, but in reality sleep is a more omnipresent factor in the health of hundreds of millions of people, far beyond the impact of virtually any other symptom one can conjure up as seemingly more prominent.

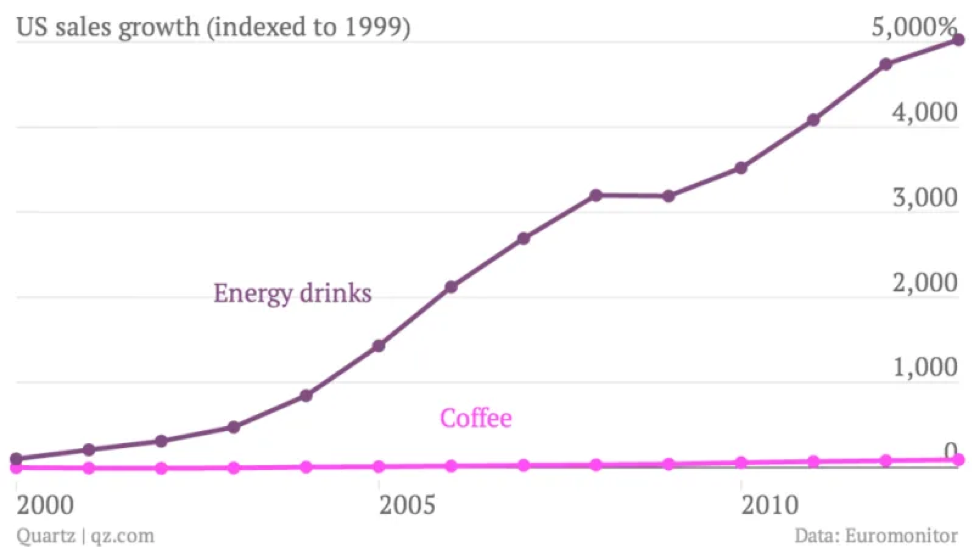

Can this disrespect be overcome? The short answer is no. Consider what is currently emphasized throughout much of society as it relates to sleep. Here are some of the most common questions that arise in conversations among the public or even among researchers. “What can I do to get by on less sleep?” “Is there a better stimulant besides caffeine?” Not only do many people view sleep in this manner, but just look at the marketplace for the explosion of so-called “energy” drinks in just one decade’s worth or recent growth. This increased consumption is described in an online public domain graph named, “Energy Drink Sales are Insane…”

Yet, don’t be fooled into thinking that coffee is no longer a big deal. Coffee consumptions currently stands at $13 billion compared to $10 billion for energy drinks, and these numbers only reflect what goes on in America. Another way to consider these facts is to ask yourself the following question: “At what point do you see Starbucks and other coffee shops going out of business?” The polite answer would seem to be “Never.”

The key here is that so many people believe that energy comes from caffeine and not from sleep.

But, if you take the time to recognize that the single most powerful internal source of human energy is sleep, then a person might begin to develop respect for the potency of his or her slumber. Think about how oxygen, food, water, and caffeine all represent something external to your body that must be ingested in some way to provide the substrate for the body to make energy or directly stimulates the brain to make energy. Even exercise, which is often described as something to generate energy, still requires a great deal of activity, that is, doing something to gain the benefit. With sleep, you hopefully lie in bed and YOU SLEEP! And, then miraculously, you wake up and have all this energy to carpe diem.

Therein lies the problem, because so many people wake up and are not ready to seize the day, due their persistent nonrestorative sleep. However, instead of connecting the Zzzzots to declare, “oh, I feel so unrested this morning, there must be something wrong with my sleep,” a huge chunk of society reaches for that first cup of coffee. As I’ve said before, I am a huge fan of caffeine in the right place and time, because caffeine consumption in whatever form is probably one of if not a leading treatment for mild depression and even more importantly, it has probably prevented literally millions of traffic and other workplace accidents in the modern era.

To talk about expanding educational efforts for providers and the public, the efforts will continue to fall short until these basic facts are drilled into society person by person. And, this type of education is not easy, because so many lifestyles all around the world, from rich to the poor, to advanced civilizations to the developing countries all show this great disrespect for sleep accompanied by a compensatory use of caffeine or other stimulants, which then further erases any need to develop some sort of “sleep awareness.”

Thus, an individual’s case of sleep apnea would need to be so severe that caffeine no longer works or if caffeine is working, the individual is suffering from some other out of control symptom, like worsening blood pressure control or intractable morning headaches or addiction to sleeping pills. One of the ironic examples here is that a great many physicians will first tell their patients to decrease caffeine consumption (instead of ordering a sleep study due to the OSA aggravation of hypertension) to see what impact such a decrease has on blood pressure readings.

The education conundrum therefore spans every aspect of the population from the public at large where individuals often complain about sleep yet know of no practical resources (except maybe the Internet) to find information or solutions, all the way up to the medical professionals who often don’t complain about their sleep and wonder why so many other people might do so.

The medical professionals are so ignorant about sleep disorders in general, they fall prey to any sort of guidance that would suggest prescription sleeping pills should solve all sleep problems. Making matters worse, the public is routinely receiving very weak or ineffectual “sleep tips” through a number of journalistic resources, including the Internet. And, often these tips lead to worse sleep problems in a great many people. Moreover, they steer people away from heading to a sleep center, the single most reliable resource for anyone who wants sleep problems taken seriously.